Trucks rumble down one of Kalamazoo’s busiest streets, Michigan Avenue, where it joins the stretch of Burdick Street known as the Kalamazoo Mall.

I’m watching the traffic with our question-asker Payton Brinks of Mattawan. Payton doesn’t particularly like Michigan Avenue. It’s one of the streets that prompted her to ask: “Why in Kalamazoo are there so many one-way streets?”

Payton’s a senior at Marietta College in Ohio. She says she wasn’t bothered by the one-way streets until she was learning how to drive. An instructor took her downtown where she discovered that navigating Kalamazoo is tricky, with its one-way arteries north, south, east, and west bound.

“There's a lot more thought that has to go into how you get from point A to point B,” said Payton, “because the city almost acts like a loop. So, you've got everything on one side, that goes one way. And if you miss it, you have to circle all the way back around, which can be kind of frustrating if you don't really know where you're going.”

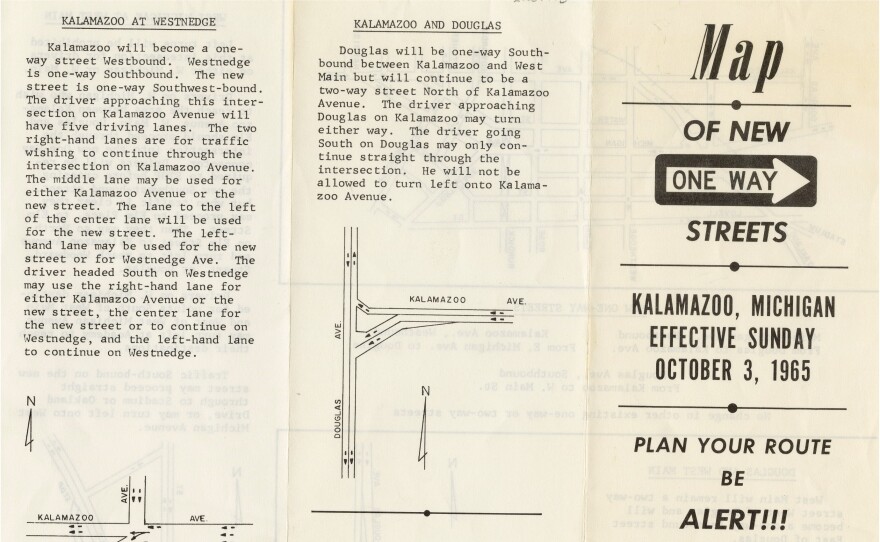

Payton’s not alone in disliking the one-ways. Dean Hauck owns the Michigan News Agency on Michigan Avenue. She says the one-way system has hurt business downtown ever since it went into effect on October 3, 1965. At the time Hauck’s stepfather owned the Michigan News. At first, he was happy the city had struck a deal for the state department of transportation to maintain Kalamazoo’s busiest streets.

“My Pop called and told me, ‘We found a wonderful solution to the fact that our streets are never maintained.’ I said, ‘What is it, Pop?’ And he said, ‘We've given our Kalamazoo and Michigan Avenue to the state.’ I said, ‘My God, what?’”

MDOT turned the roads into one-way trunk lines. It widened the lanes, took out crosswalks and increased speeds by 11 miles an hour. Hauck says the changes made it harder for customers to stop at the Michigan News. She says the conversion almost cost her stepfather his business.

“You look at the books from the Michigan News, it immediately shows that was a hideous choice,” said Hauck. “People are flying by, as a matter of fact, to get to their job on the other side of the city. He saw half as many people, he saw $200 to $300 less a day. People calling him saying ‘what have you done? I can’t even get to your store anymore.'”

But after decades of complaints, things are starting to change.

Back on the Kalamazoo Mall, our question-asker, Payton, and I meet up with Kalamazoo City officials to find out why MDOT converted the streets to one-way traffic.

“Their whole system of measurement for success was speed, stops, delay. And they achieved those. People went faster, they stopped less and there was less delay. And that was what they were interested in,” said Dennis Randolph, the city’s traffic engineer.

MDOT’s one-way system helped cars and trucks get through the city and onto the interstate more quickly. But Randolph says it made downtown less accessible to surrounding neighborhoods, and created a hostile environment for anyone not in a car. Standing next to Michigan Avenue, where traffic volume averages 17,786 cars and trucks a day, Randolph watched as semi-trucks streamed by.

“It is tough to want to step out onto that street. You know with trucks, you can see that — trucks going 40 or 50 miles an hour down here. It's not very inviting. As a traffic engineer, I shudder when I see that,” said Randolph. “And the noise, you can hardly stand here because of the noise.”

A more inviting Kalamazoo became possible in 2019, when the city regained control of the streets from MDOT. Work is underway to create what city officials call a “connected city” with “streets for all.”

Construction crews are working to calm traffic on Stadium Drive by adding a landscaped median, better crosswalk signals and more sidewalks. Work to calm Westnedge Avenue from Dunkley Street to Michigan Avenue began Monday. Pavement markings will be repainted to right-size vehicle lanes at 11 feet; bike lanes and designated parking areas will also be added.

Public Works Division Manager Anthony Ladd said Kalamazoo and Michigan Avenues will be converted back to two-way streets.

“We want to create more of a main street feel to it, one that you're likely more familiar with. Something that's more inviting,” Ladd said, talking about Michigan Avenue.

But while making the streets one-way was relatively easy, un-doing that system won’t be. The city says it will take two years just to design the new Kalamazoo Avenue, the first two-way conversion planned. It will take another two years to convert it. Michigan Avenue’s design process begins next year.

Our Why’s That? question asker Payton Brinks says she’s glad the city will re-embrace two-way streets.

“I'm not a city planning expert, but I definitely like the idea of keeping Kalamazoo very walkable,” she said.

For more information about the plan, “Streets for All: Creating a Connected City”, along with other city projects in the works, go to the Imagine Kalamazoo 2025 website.